Greenland’s massive ice sheet may have melted by a record amount this year, scientists have warned.

During this year alone, it lost enough ice to raise the average global sea level by more than a millimetre.

Researchers say they’re “astounded” by the acceleration in melting and fear for the future of cities on coasts around the world.

One glacier in southern Greenland has thinned by as much as 100 metres since I last filmed on it back in 2004.

Why does Greenland matter?

Essentially because its ice sheet is seven times the area of the UK and up to 2-3km thick in places. It stores so much frozen water that if the whole thing melted, it would raise sea levels worldwide by up to 7m.

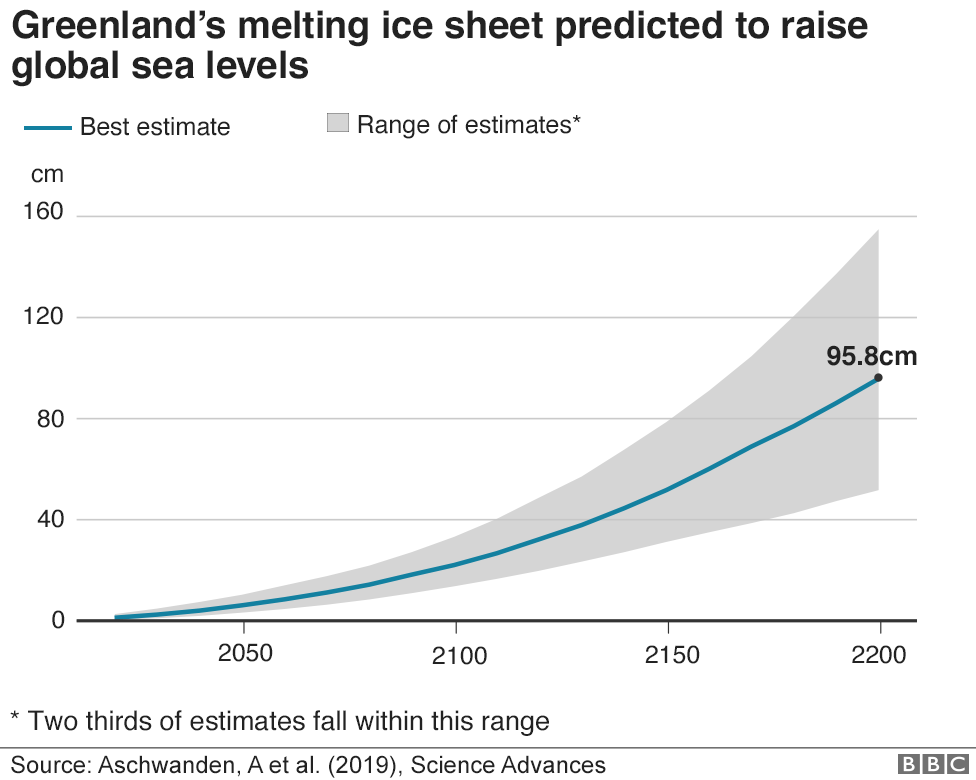

No one is suggesting that could happen for hundreds or even thousands of years but even a small increase in the rate of melting in coming decades could threaten millions of people living in low-lying areas.

Bangladesh, Florida, and eastern England are among many areas known to be particularly vulnerable to rises in sea level over the course of the century.

And although the island of Greenland is remote, stretching from the north of the Atlantic high into the Arctic, its fate could have major implications for the severity of future flooding and may even alter coastlines and force communities to move inland.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

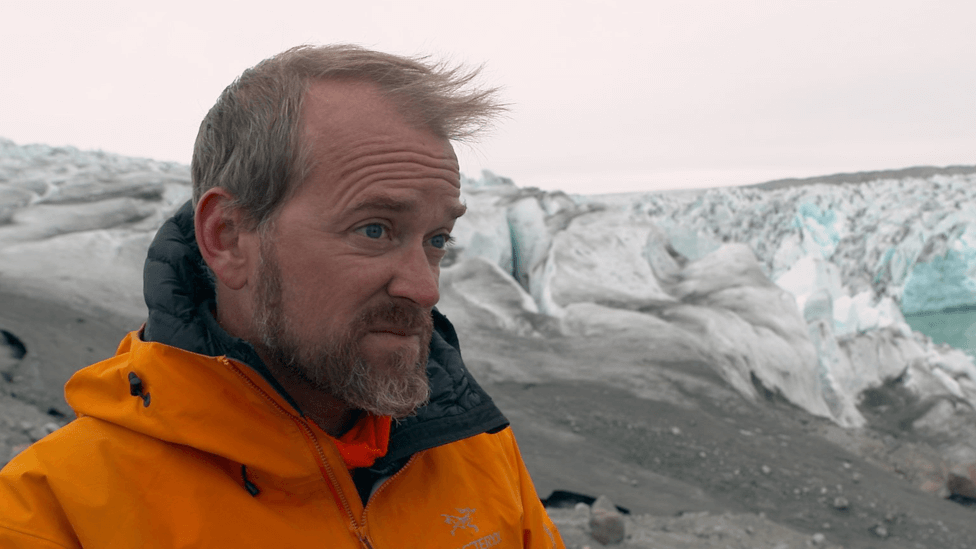

One of the scientists studying the ice sheet, Dr Jason Box of the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS), says he’s unnerved by the potential dangers and that coastal planners need to “brace themselves”.

“Now that I’m starting to understand more of the consequences, it’s actually keeping me awake at night because I realise the significance of this place around the world and the livelihoods that are already affected by sea level rise,” he told me.

Dr Jason Box, Geological Survey of Denmark

How much is Greenland melting?

Until recently, the ice sheet was generally in a state of balance – the amount of snow falling in winter was roughly equal to the amount of ice melting in summer.

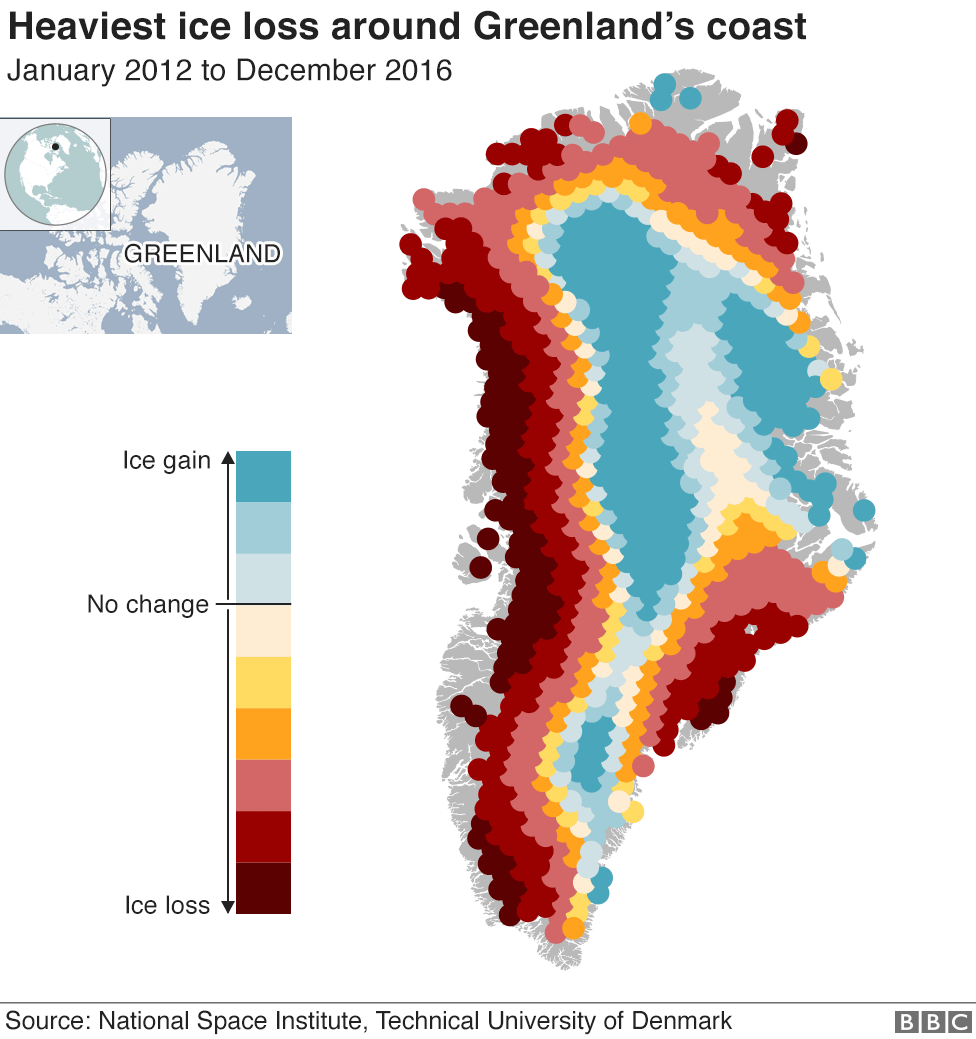

Last year, there was actually a gain in ice but that was relatively unusual. Over the last 30 years, decade-by-decade, Greenland has tended to shed more ice.

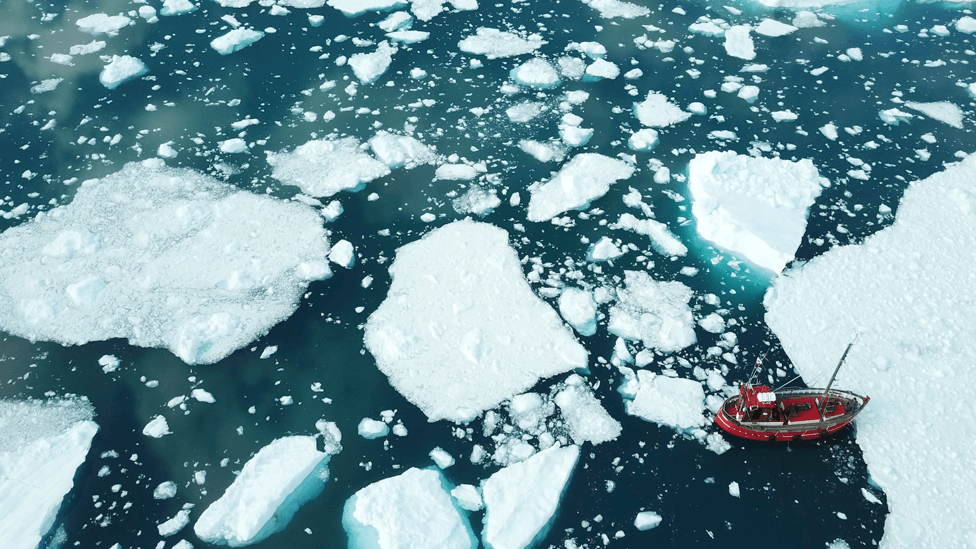

Either the ice melts at the surface which sends torrents of water down to the surrounding seas or huge chunks of ice break off from the margins and float away as icebergs, gradually to melt.

Recent years have seen hundreds of billions of tonnes of ice lost – and a rough guide to the effect on sea level is that 362 billion tonnes of melt raises the average ocean level by a millimetre.

That doesn’t sound a lot but in 2012 Greenland’s loss totalled about 450 billion tonnes, and this year’s melt is on course to produce about the same, or even slightly more, with some researchers suggesting it could raise sea levels by up to 2mm.

And on top of that you have to factor in the ice melting in Antarctica plus the effect of water expanding as it warms. It all raises the level of the oceans.

According to Dr Box, it’s the recent increase in the average temperature that’s being felt in Greenland’s ice: “Already effectively that’s a death sentence for the Greenland ice sheet because also going forward in time we’re expecting temperatures only to climb,” he said.

“So, we’re losing Greenland – it’s really a question of how fast.”

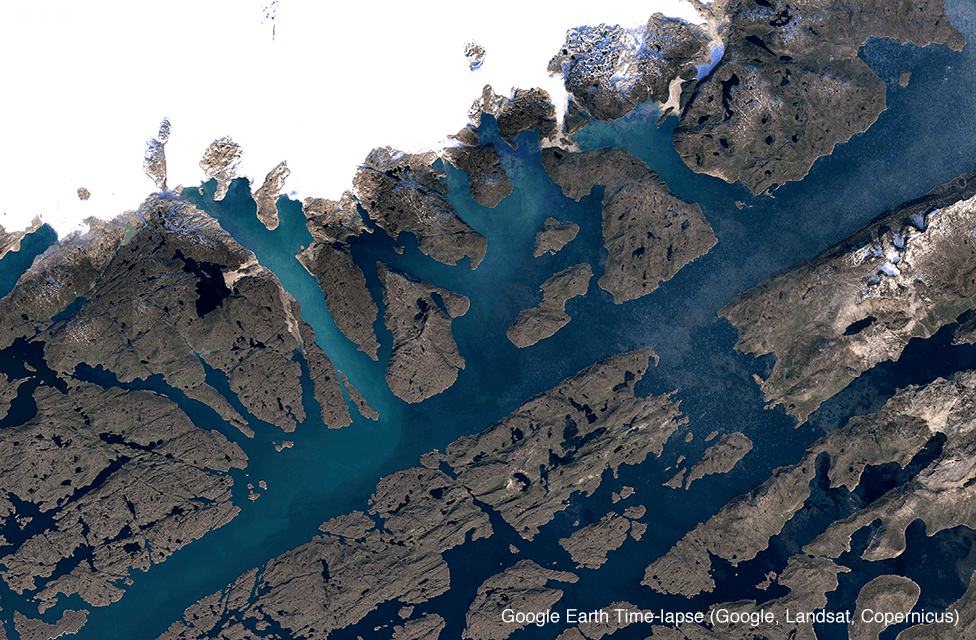

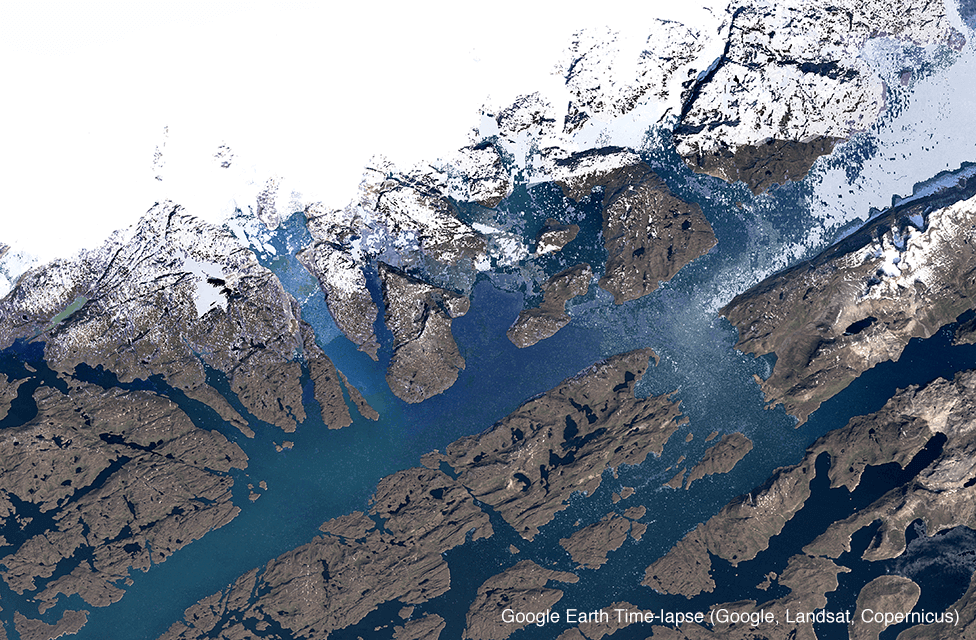

How rapidly is the ice sheet changing?

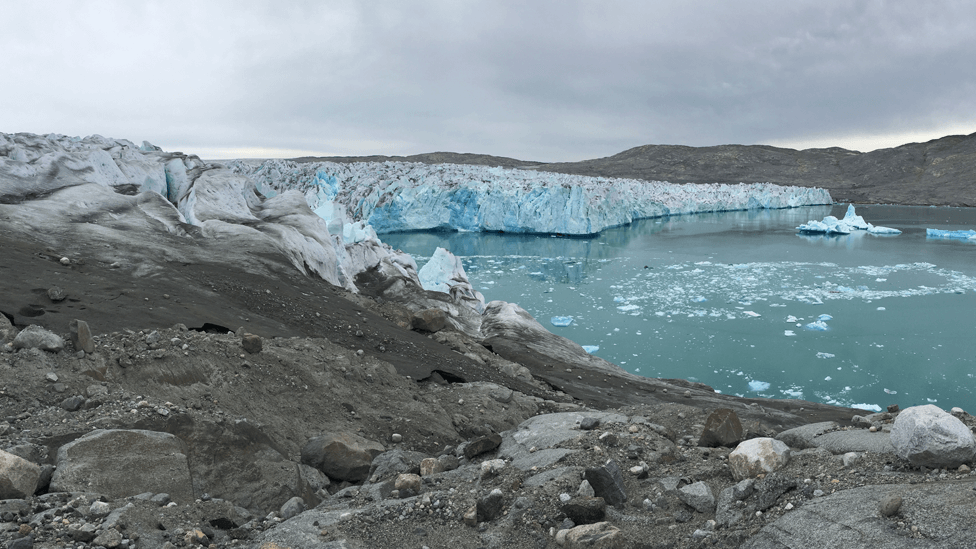

I’ve seen for myself what’s happened to one corner of it. Sermilik glacier at the southern end is not one of Greenland’s largest but it does rank as one of the fastest-shrinking streams of ice anywhere in the world.

To reach it back in 2004, we flew past towering cliffs of ice, the front of the glacier an immense wall of pale grey and blue standing high above the sea.

At that time, we accompanied a scientist who checked instruments positioned on the ice and he was stunned to see how the surface of the glacier was dropping by as much as a metre every month.

And over the past 15 years, that rate of shrinking has continued so aggressively that now, on a return visit to the same glacier, the ice looks diminished, almost battered, and far less dominating in the landscape.

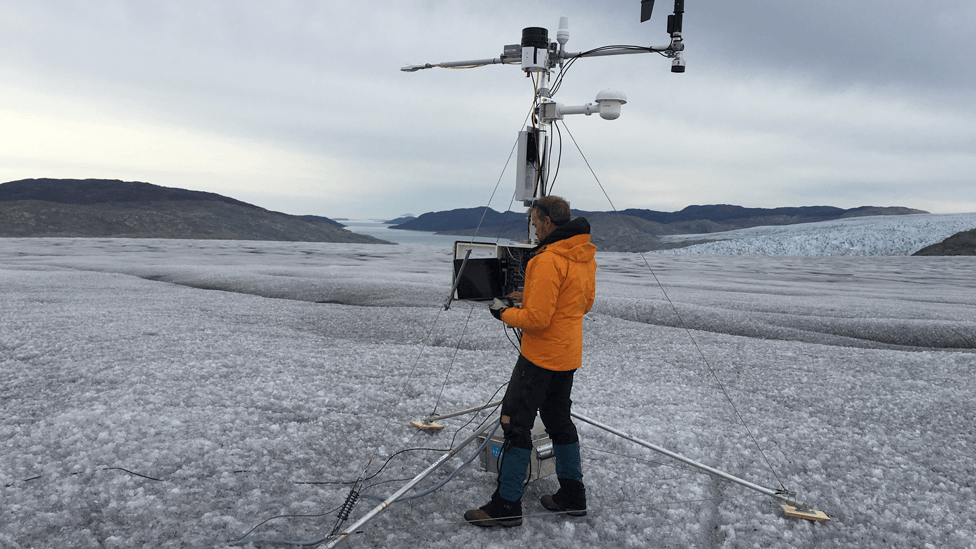

Jason Box is with me and he gathers the latest readings which show that over this summer alone the glacier has shrunk by an estimated 9m. “That’s an astounding rate of loss,” he said.

Since my last visit, the surface of this margin of the ice sheet has lowered by an extraordinary 100m, more than halving in thickness, exposing the remaining ice to the relatively warmer temperatures of lower altitudes.

What’s happening to the ice itself?

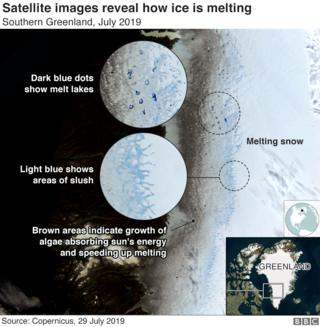

While you might think of the Arctic as a pristine white landscape, the startling feature of the surface is how dirty it looks. Walking on it feels like arriving on the Moon.

There are big areas of pale grey and smaller patches that are much darker, covered with what appears to be mud or silt – it’s a grim and rather depressing sight.

Algae growing on the Sermilik glacier

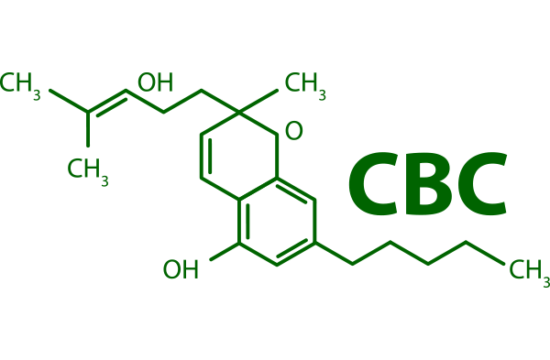

It used to be thought that this darkness was mainly caused by a mix of dust and pollution particles carried on the winds from distant power stations and industrial centres.

But since my last visit to Sermilik glacier, scientists have made an important breakthrough in understanding that a major cause of the darkening is in fact biological – algae, microscopically small plants that are flourishing in the melting ice.

By turning the surface grey, or black, from its usual bright white, the algae make it less reflective, so it absorbs more of the Sun’s rays. This accelerates the warming and in turn leads to even more melting.

Who’s trying to work out what’s going on?

With the stakes so high for so many millions of people around the world, Greenland is the target of a major international research effort involving satellites, monitoring flights and expeditions on the ice itself.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

The US space agency Nasa has for years run projects investigating exactly what’s causing the ice to melt and what could happen to it in future.

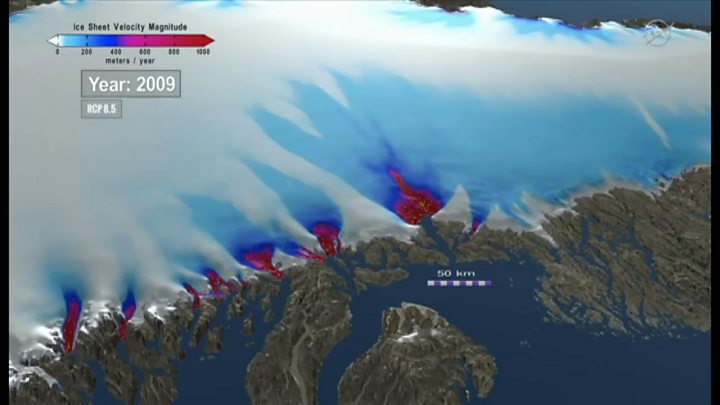

Back in 2005, I reported on a Nasa-funded team that made an important discovery about the movement of the ice sheet.

Although the great mass of ice looks immobile, it’s actually always inching down towards the coast and the team found that this movement doubles in speed in summer – as meltwater from the surface works its way to the bottom of the ice and helps it to slide along.

Another revelation is that the ice is not only being melted by the air, as the atmosphere heats up, but also by warmer water reaching underneath the fronts of the glaciers. One Nasa scientist describes the ice as being under a hair-dryer and at the same time also on a cooker.

And Jason Box and his colleagues at GEUS run a network of sensors on the ice to record details of the height of the surface and its reflectivity, and how they’re changing.

The hardest challenge for the scientific community is understanding enough of the mechanisms of the ice sheet to be able to offer reliable forecasts of sea level rise.

Dr Masashi Niwano, a researcher with the Japan Meteorological Agency, is just back from a field trip to gather data to try to validate his computer simulations of the ice.

“The ice sheet mass is decreasing – that is very certain. And these results affect global sea-level rise – that is also very certain,” he said.

“But maybe there are several physical processes that we don’t understand, so developing future projections is very difficult.”

What do the people of Greenland make of all this?

There are only 56,000 Greenlanders, and they live in communities perched on the narrow band of land at the edge of the ice sheet which, though close, is usually out of sight.

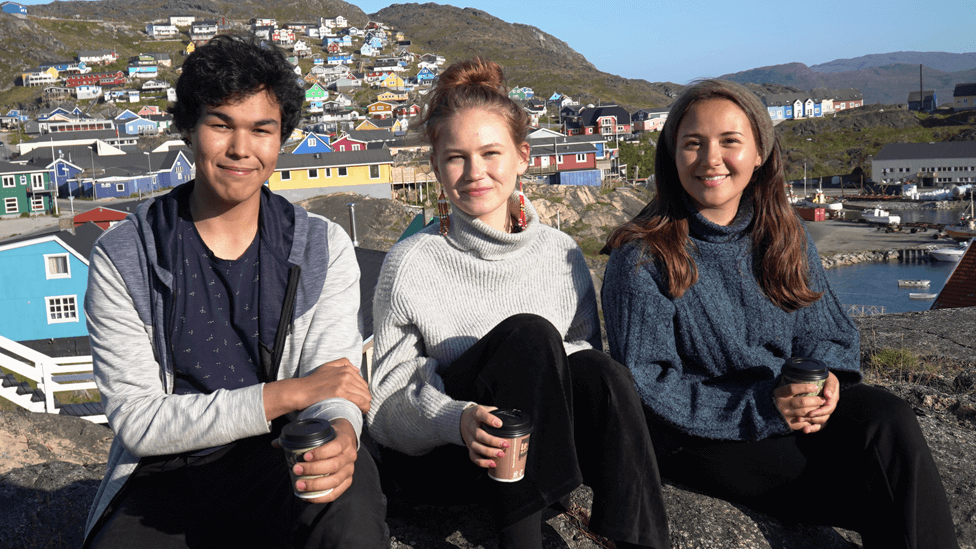

Inutsiaq Ibsen, 18, Naja-Theresia Høegh, 19, and Caroline Hartmann Hansen, 21, in Qaqortoq

In the village of Narsaq, Christian Mortensen tells me a glacier that was visible when he was younger has since retreated and that icebergs seem to “break more and more” into the waters.

Warmer conditions would allow more farming and, as we talk, cattle are grazing around us on pasture that’s beside bright white chunks of ice bobbing in the sea.

But for some young Greenlanders, climate change is becoming a big concern, partly because of the impact of “their” ice on other areas of the planet.

Naja-Theresia Høegh, who’s just finished school, was inspired by the Swedish campaigner Greta Thunberg to lead a climate strike in her town of Qaqortoq, a pretty port of brightly painted houses.

She describes a boat trip to the edge of the ice sheet where she found it “astonishing and scary” that so much water could flow out.

“All of that is ending up in our waters, into the sea, and to the rest of the world and, if this continues, it will someday just cover a whole country,” Ms Høegh explained.

Her friend Caroline Hartmann Hansen also talked about her fears over the uncontrolled nature of the melting. “It’s not our fault; it’s everyone’s,” she said.

Can anything be done?

If the calculations of Jason Box and his colleagues are right, the ice sheet is already crossing a threshold into an era in which there may still be years with net gains of ice – like last year – but the new normal will see more big losses.

Even with a rapid move to cut emissions of warming gases – as outlined in the 2015 Paris climate agreement – Greenland could still see a growing rate of melting, though that could possibly be slowed.

So, as with the young Greenland climate campaigners, the scientists feel the need to take action of their own.

They have started a scheme to try to absorb some of the carbon dioxide emitted by the flights they take to conduct their research; Jason said he has been criticised for his high carbon footprint and “feels guilty about it”.

Dr Faezeh Nick plants tree saplings near Narsarsuaq

Close to the airport at Narsarsuaq, which connects them to the glaciers of southern Greenland, the researchers are planting 6,000 saplings of Siberian larch, a type of tree known to do well in conditions here.

They admit that 10 of the trees would need to grow for 60 years to absorb the carbon produced by a return flight from London to San Francisco, but they say it’s a start and that if the project later leads to a much larger forest, it might “make a dent” in climate change.

Meanwhile, as memories of last month’s polar heatwave fade, the scientists are leaving ahead of the winter nights, to try to hone their predictions for what the scarred and darkened ice sheet is likely do next.

Follow David on Twitter.

Produced by David Brown, Robert Magee, Kate Stephens and Nassos Stylianou. Edited by Paul Rincon and Jonathan Amos.