Climate change will exact a toll on global economic output as higher temperatures hamstring industries from farming to manufacturing, according to a new study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Record-breaking heat across the globe made headlines throughout July, and now researchers say a persistent increase in average global temperature by 0.04 degrees Celsius per year, barring major policy breakthroughs, is set to reduce world real GDP per capita by 7.22% by 2100.

The researchers — hailing from the International Monetary Fund, the University of Cambridge and the University of Southern California — found little evidence that precipitation had an impact on GDP, but instead observed a large temperature-related effect.

The U.S. is expected to see its GDP per capita decline 10.5%, China’s by 4.3% and the European Union’s by 4.6% over the next 81 years as a result of temperature fluctuations. In other words, if global GDP doubles or halves by 2100, the results suggest real GDP per capita would still be 7.22% below where it would be otherwise.

In the nearer term, and assuming no major policy changes and continued greenhouse emissions, the climate-related drag on global GDP per capita is projected to surpass 2.5% and exceed 3.7% in the U.S. by 2050.

“A persistent above-norm increase in average global temperature by 0.04 Celsius per year leads to substantial output losses, reducing real per capita output by 0.8%, 2.51% and 7.22% percent in 2030, 2050 and 2100, respectively,” the researchers wrote. “Furthermore, we show that our empirical findings apply equally to poor or rich, and hot or cold countries.”

Using a panel data set of 174 countries over the years 1960 to 2014, the team tested two scenarios. The first tested the impact of climate change in the absence of climate change policies (known as “RCP 8.5” in the table), implying an annual increase of 0.04 degrees Celsius.

The other scenario corresponded to the December 2015 Paris Agreement that President Donald Trump decided to abandoned (known as “RCP 2.6” in the table). That scenario implies an annual increase of 0.01 degrees Celsius.

In the first scenario, which assumes an increase in average global temperate of 0.04 degrees Celsius, the researchers found that the U.S. faces a GDP decline above 10% by 2100 if global temperatures continue to rise at their historic pace. In the second scenario, which abides by the Paris Agreement’s global annual temperature increase of 0.01 degrees Celsius, the U.S. would still see a comparatively large, albeit smaller 1.88% GDP reduction.

Part of the outsized impact is due to the fact that temperatures in the U.S. are rising faster than the rest of the world, the researchers wrote, with the nation’s average annual increase of 0.026 degrees Celsius well above the globe’s 0.018-degree annual average.

“Our results provided evidence for the damage climate change causes in the United States using [gross state product], GSP per capita, labour productivity, and employment as well as output growth in ten economic sectors,” the researchers wrote.

Long-run GDP Impact by Region

Source: “Long-term Macroeconomic Effects of Climate Change” (2019), Kahn et al.

“While certain sectors in the U.S. economy might have adapted to higher temperatures, economic activity in the U.S. overall and at the sectoral level continues to be sensitive to deviations of temperature and precipitation from their historical norms.”

Countries that derive a large proportion of their GDP from agriculture could be most at risk. Excessive heat or rainfall can not only kill crops like corn and soybeans, but delay fieldwork and stall equipment shipments.

Though the new study did not find evidence that increased rain damages economic growth, one business leader says increased precipitation can dampen profits. Commenting on Friday, the chief economist at farm equipment maker Deere noted that doubts surrounding crop production have already weighed on government corn production estimates.

“The wettest 12-month period in U.S. history brought flooding and record planting delays across major corn and soybean growing regions,” Luke Chandler said on Deere’s fiscal third-quarter earnings call. “The result was heightened uncertainty around row crop production.”

“This uncertainty was reflected in the USDA’s latest estimates released this past Monday, which surprised the market, particularly the forecast of national corn production,” he added. The U.S. Department of Agriculture reported on Aug. 12 that soybean production is down 19 percent from 2018 while corn growers are expected to decrease their production 4 percent from last year.

But relief from the unusual weather looks unlikely. The recent deluge of recent meteorological data shows a persistent pattern of record-breaking heat.

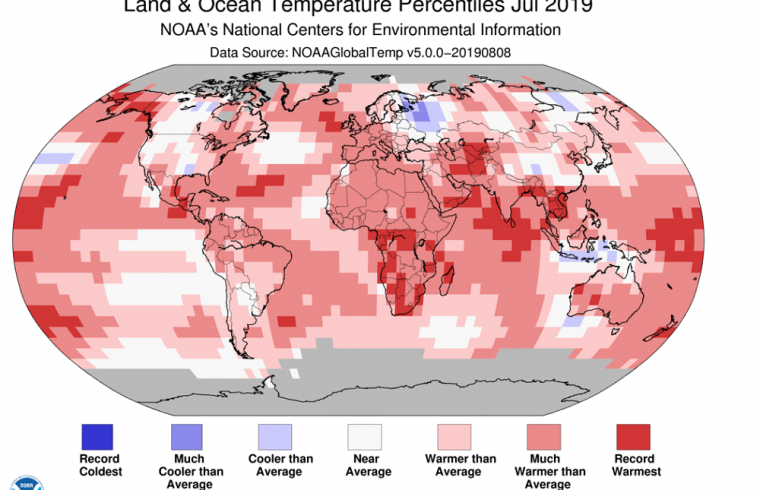

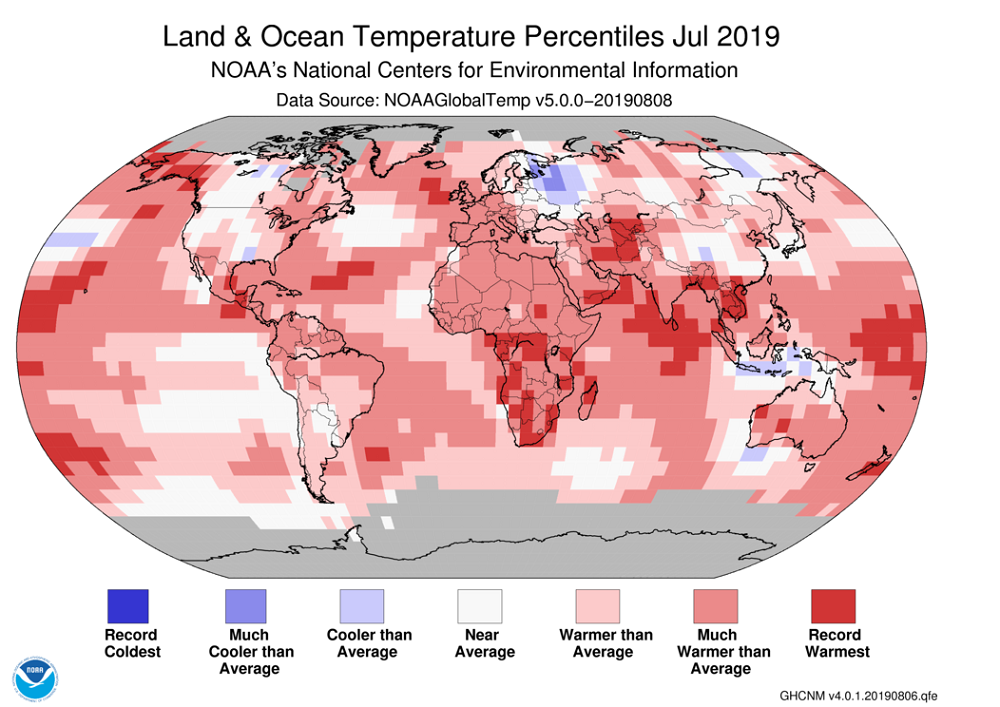

The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced on Thursday that July was the hottest month ever recorded, shrinking the Arctic and Antarctic sea ice to historic lows.

The 2015 Paris Agreement seeks to combat those effects: It was designed to prevent global temperatures from rising by more than 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. It mandates 195 national signatories — nearly every country in the world — to devise a plans to cut emissions in an attempt to stem the impact of climate change.

The average global temperature in July was 1.71 degrees Fahrenheit above the 20th-century average of 60.4 degrees, making it the hottest July in the 140-year record. Meanwhile, nine of the 10 hottest Julys have occurred since 2005, with the last five years ranking as the five hottest.